Comprehensive Guide to VoIP Voice Quality

| Quick Navigation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Degradation Factors | Measurement Methods | Practical Monitoring |

|

Traditional Impairments

IP Network Impairments |

Subjective Methods Objective Methods Parametric Model |

VoIPmonitor Features |

This comprehensive guide details voice quality degradation factors in telephony and VoIP networks, measurement methods, and practical monitoring with VoIPmonitor.

Introduction

Voice over IP (VoIP) has become a dominant technology for telephony, merging the world of traditional telephones with IP networks. Ensuring high voice quality in VoIP is critical for user satisfaction and successful network operation. Unlike legacy circuit-switched telephony, IP networks introduce new challenges such as variable packet delay and packet loss, which can significantly degrade call quality. Understanding all the factors that impair voice transmission – from analog acoustics to digital network issues – is essential for telecommunications professionals.

In this comprehensive guide, we detail the myriad of voice quality degradation factors and how they map to measurable parameters. We then explore both subjective and objective metrics for quantifying voice quality, including the well-known Mean Opinion Score (MOS) and modern evaluation methods like PESQ, POLQA, and the ITU E-model. Throughout, we reference relevant ITU-T and IETF standards to ground the discussion in current international recommendations.

Crucially, we also demonstrate how these concepts apply in practice, with a focus on VoIPmonitor – a specialized VoIP monitoring tool. VoIPmonitor offers unique capabilities for analyzing call quality: detailed jitter and Packet Delay Variation (PDV) statistics, jitter buffer behavior simulation, MOS score computation, and even detection of audio clipping and silence periods. By leveraging passive monitoring of live calls, VoIPmonitor can alert operators to quality issues in real time and provide forensic data to troubleshoot problems.

This guide is intended as a full-length professional resource for telecom and VoIP engineers. It assumes a technical background and aims to be as detailed and up-to-date as possible. Whether you're designing a network, operating a VoIP service, or developing monitoring solutions, this article will serve as a valuable reference on voice transmission quality in IP networks and how to measure and assure it.

Voice Quality Degradation Factors

In any voice communication system – traditional or VoIP – there are numerous factors that can degrade the quality of the speech heard by users. These range from acoustic and analog impairments in the endpoints to network-induced impairments in packet-switched transport. Below we examine all key degradation factors in detail, explaining their nature and how they affect perceived quality. We also note how each factor can be measured or quantified, either via objective metrics or through standards-based parameters.

Volume (Loudness) Level

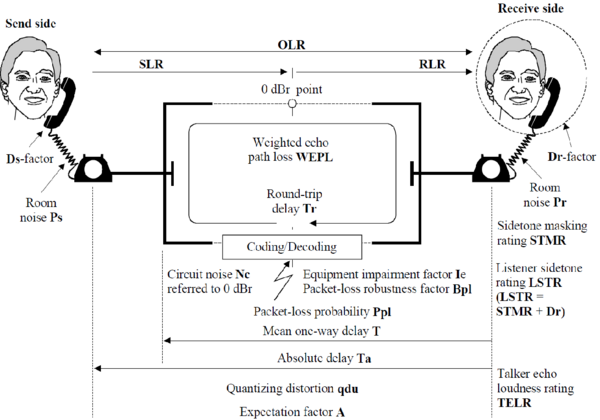

Description: The loudness level of the voice signal is critical for clear communication. If the volume is too low, the speech may be hard to discern; if too high, it can cause discomfort or even distortion. In telephony engineering, loudness is quantified using Loudness Ratings. The Send Loudness Rating (SLR) measures the talker's side volume level (microphone gain and telephone set output), and the Receive Loudness Rating (RLR) measures the listener's side volume (earphone sensitivity). A mismatch in loudness levels between endpoints can cause one party's voice to be too quiet or too loud for the other party.

The Overall Loudness Rating (OLR) is the sum of SLR and RLR:

According to ITU-T recommendations:

- Optimal OLR range: 5-15 dB

- Values below 5 dB cause discomfort due to excessive loudness

- Values above 15 dB make speech difficult to understand

Impacts on Quality: Suboptimal loudness leads to user frustration: low volume causes the listener to strain to hear, while excessive volume can be perceived as shouting or can introduce distortion. Very high levels might also trigger echo or feedback in some systems.

Measurement: Loudness is measured in decibels relative to a reference level. The ITU-T recommends nominal SLR and RLR values for telephone terminals to ensure comfortable listening. In objective planning, one might target an overall Operational Loudness Rating (OLR) that falls within a range that yields a good loudness MOS. Modern digital VoIP phones generally adhere to these loudness standards, but misconfigurations (like incorrect gain settings) can still occur. In testing, one can use test signals and measure levels in dBm0 or use an analog loudness rating measurement per ITU-T P.79.

Mitigation: Proper calibration of device gains and using automatic level control can keep volume levels within optimum range.

Circuit Noise and Background Noise

Description: Circuit noise refers to the electrical noise present in the communication path, even when no one is speaking. In traditional telephony, this could be a low-level hiss or hum on the line (often measured as circuit noise in dBrn). In VoIP, digital circuits themselves do not add audible hiss, but background noise from the environment or analog interfaces (microphone noise, room ambiance) still affects call quality. Background noise is the ambient sound at the caller or callee's location – for example, office chatter, traffic noise, or wind – that gets picked up and transmitted along with speech.

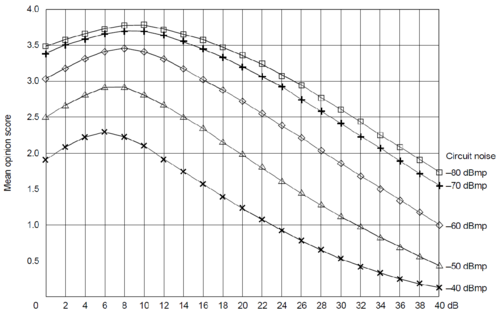

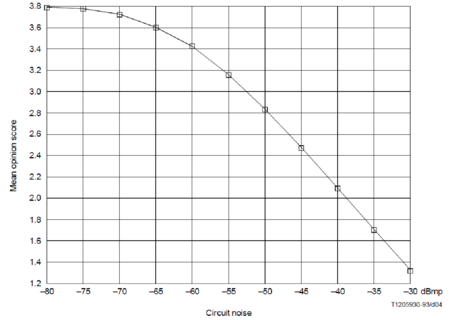

Impacts on Quality: Noise competes with speech for the listener's attention, effectively reducing the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). High background or circuit noise can mask parts of speech, making conversation tiring. If noise is too loud, important speech sounds (especially softer consonants) may be missed by the listener. In subjective terms, excessive noise contributes to listener fatigue and lower quality ratings.

Measurement: Noise level is typically measured in decibels. Circuit noise in telecom is often measured with a weighted filter (e.g., C-message weighting in analog lines, or psophometric weighting) and expressed in dBm0p (decibels referred to 0 dBm, psophometric). For background noise, one can measure the noise floor in the absence of speech. The E-model (ITU-T G.107) includes parameters for send-side and receive-side noise levels (denoted as and ), which contribute to the transmission rating. Acceptable background noise for comfortable conversation is generally < 30 dBA in a quiet environment. Beyond that, MOS ratings start to drop. VoIP systems often employ noise suppression algorithms to reduce background noise transmission.

| Noise Level (dBmp) | Quality Impact |

|---|---|

| -80 to -70 | Negligible impact |

| -70 to -65 | Minor degradation |

| -65 to -55 | Noticeable degradation |

| -55 to -40 | Significant degradation |

| > -40 | Severe degradation |

Mitigation: Use of noise-cancelling microphones, acoustic treatments in loud environments, and digital noise reduction algorithms can lower the noise that is sent across the call. On analog gateways, ensuring good shielding and proper impedance matching can reduce hum and hiss.

Sidetone (Local Loop Feedback)

Description: Sidetone is the phenomenon where a talker hears a small portion of their own voice in their telephone earpiece as they speak. In traditional analog phones, sidetone is deliberately introduced via the phone's hybrid circuit – it's essentially a form of immediate echo that reassures the speaker that the phone is working and allows them to modulate their speaking volume naturally. The sidetone needs to be at an appropriate level: too low and the user feels like talking into a dead phone; too high and it becomes a loud echo of one's own voice.

Impacts on Quality: Sidetone primarily affects the talker's comfort. Proper sidetone makes speaking feel more natural and prevents the talker from inadvertently shouting (if they hear no feedback, they may speak louder than necessary). Excessive sidetone, however, can be distracting or annoying (like hearing an echo of yourself immediately). While sidetone doesn't directly impair the listener's experience, it indirectly influences call quality by affecting how the talker behaves. Very poor sidetone (either none or far too much) can lead to lower conversational quality scores in subjective tests.

Measurement: Sidetone level is quantified by the Sidetone Masking Rating (STMR). STMR is defined in ITU-T recommendations as the measure of how much the talker's own voice is reduced (masked) in the feedback they hear:

- Optimal STMR: 8-12 dB

- Higher STMR (excessive loss of sidetone) means very weak sidetone

- Lower STMR means strong sidetone (potentially too loud)

Sidetone characteristics are usually engineered into telephone handsets, but VoIP softphones or headsets might not provide sidetone unless simulated in software.

Mitigation: In VoIP endpoints, if users complain of "not hearing themselves," some softphone or headset settings provide a sidetone mix. Conversely, if sidetone is too loud (which is rare in digital endpoints unless feedback loops exist), it would require adjusting device firmware.

Frequency Response and Attenuation Distortion

Description: Frequency response refers to how evenly the communication channel transmits different audio frequencies. The human voice spans roughly 300 Hz to 3400 Hz in traditional telephony (narrowband PSTN quality), and up to about 7 kHz for wideband voice. Attenuation distortion occurs if some frequency components of speech are attenuated more than others during transmission. For example, if high frequencies are not transmitted well, speech will sound muffled; if low frequencies drop off, speech may sound thin. Classic analog lines and telephony equipment specified a frequency response tolerance (e.g., within ±x dB over the voice band).

In digital codecs, frequency response is dictated by the codec's design and sampling rate:

- G.711 (narrowband) covers up to ~3.4 kHz

- G.722 (wideband) covers up to 7 kHz, giving more natural sound

Impacts on Quality: Uneven frequency response can reduce intelligibility. Critical speech components (like sibilants in the high frequencies or vowel formants in mid frequencies) might be weakened, making it harder to distinguish sounds. Muffled audio (loss of highs) often yields lower MOS because it's simply harder to understand, even if loudness is sufficient. Conversely, over-emphasis of certain frequencies can make the sound harsh or cause circuit resonance. A flat frequency response within the necessary band yields the best quality for that band limit. Wideband audio (50–7000 Hz) significantly improves perceived clarity and naturalness, which is why HD Voice services using codecs like G.722 or Opus achieve higher MOS than narrowband G.711 under the same conditions.

Measurement: Frequency response is measured by sending test tones or speech spectra and measuring the gain vs frequency. Telephony standards like ITU-T G.122 and G.130 specified acceptable attenuation distortion (e.g., within ±1 or 2 dB across 300–3400 Hz). Modern digital systems either meet these inherently or intentionally band-limit for known reasons (like narrowband codecs). Subjectively, poor frequency response shows up in MOS tests as lower scores on "clarity" even if no noise or loss is present.

Mitigation: Using wideband codecs where possible is the primary way to improve frequency-related quality. Ensure that any analog components (microphones, speakers, analog gateways) have appropriate frequency handling. Avoid using overly aggressive filters or low-bitrate codecs that truncate important frequency content unless necessary for bandwidth.

Group Delay Distortion

Description: Group delay distortion refers to frequency-dependent delay – i.e., when some frequency components of the signal are delayed more than others. In an ideal system, all frequency components of a voice signal would experience the same propagation delay. However, certain filters or network elements might introduce varying delays across the spectrum. The result can be phase distortion of the voice signal, which particularly affects the shape of speech waveforms.

In analog long-distance systems (like multiplexed carrier systems), group delay distortion was a concern; for example, frequencies at the edge of the band might be delayed slightly more. In modern digital VoIP, group delay distortion is usually negligible inside a codec's passband, but if acoustic echoes or frequency-specific processing occur, it could contribute subtly.

Impacts on Quality: Minor group delay distortion is generally not perceptible by users on its own. However, in severe cases, it can smear speech transients (making speech sound slightly "slurred" or less crisp). Historically, if group delay distortion exceeded certain thresholds, it could degrade the quality rating, especially in combination with other impairments. In most VoIP scenarios, this is not a dominant factor – codecs typically preserve phase well within the band, and network delays are frequency-independent (packets affect all frequencies equally).

Measurement: Group delay distortion can be measured by sending test pulses or multi-frequency signals and measuring delay as a function of frequency. It is usually expressed in milliseconds of variation across the band. For example, older ITU specs might have said something like "not more than 1 ms variation in delay from 500–2800 Hz" for toll-quality circuits. In E-model terms, group delay distortion isn't explicitly parameterized; it would typically be subsumed under general frequency response or just not considered if within nominal limits.

Mitigation: Using modern digital equipment essentially mitigates this – good design of filters (e.g., linear phase filters) ensures minimal group delay distortion. If one were chaining multiple analog devices or filters, ensuring each is well-equalized would help. In essence, this factor is mentioned for completeness but is rarely a standalone issue in today's VoIP telephony.

Absolute Delay (Latency)

Description: Absolute delay is the end-to-end one-way transit time from the speaker's mouth to the listener's ear. In VoIP, this includes all sources of latency:

- Codec delay – encoding/decoding processing time

- Packetization delay – assembling voice samples into packets

- Network propagation delay – transmission through the IP network

- Jitter buffer delay – buffering to smooth packet arrival variations

- Playout delay – final processing and D/A conversion

Unlike the delay distortion above, absolute delay affects the conversational dynamic but not the audible fidelity of individual words.

Impacts on Quality: Humans are very sensitive to conversational delay. Small one-way delays (say < 100 ms) are almost unnoticeable and cause no harm to normal conversation. As delay increases into the few hundreds of milliseconds, it begins to disrupt the conversational interaction – you start hearing the other person's responses later than expected, which can lead to awkward pauses, interruptions (talker overlap), and the feeling that the call is "laggy." Very high delays (> 500 ms one-way) make natural conversation nearly impossible – parties will frequently double-talk (both speak at once without realizing) or leave long gaps waiting for responses, often leading to confusion.

Importantly, delay also amplifies the perception of echo. If an echo is present, a short delay echo (< 20 ms) just sounds like sidetone; but a longer delay echo (say 100+ ms) becomes distinctly audible and highly annoying. So absolute latency and echo interplay is crucial: even a low-level echo can be tolerated if it returns almost immediately, but if it comes back after a significant delay, it will disturb the talker. Thus, network planners aim to minimize one-way delay not just for conversational smoothness but also to avoid echo issues (or ensure echo cancellers have enough time span to cover the delay).

| One-way Delay | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|

| 0-150 ms | Acceptable for most applications (essentially unnoticeable or only slightly noticeable) |

| 150-400 ms | Acceptable but may impact conversation flow; at the limit of many echo cancellers |

| > 400 ms | Generally unacceptable for two-way conversation |

Measurement: One-way delay can be measured with synchronized endpoints or by using protocols like RTCP that can report timing. In a live VoIP call, measuring one-way delay precisely is challenging unless both endpoints or measurement points are time-synchronized (for example, using NTP or GPS timing). Often, only round-trip delay is measured (e.g., via ping or RTCP round-trip time) and one-way is inferred by halving if path is symmetric. VoIPmonitor, for instance, focuses more on relative delay variation (jitter) since absolute one-way delay requires special instrumentation; however, if both call legs are captured, it can estimate differences in timing between streams.

Mitigation: To control latency, one should minimize unnecessary buffering (while still using enough jitter buffer to handle jitter), use faster networks/QoS for propagation, and avoid long serialization delays (e.g., use appropriate packetization – smaller packets reduce per-packet serialization delay at the cost of overhead). Many VoIP codecs add some algorithmic delay (lookahead, frame size); using a low-delay codec can help if latency is critical. For echo, deploy echo cancellers (per ITU-T G.168) in gateways or phones to remove line echo up to the expected tail length. Well-implemented echo cancellation is essential especially when delays are moderately high.

Echo (Talker Echo and Listener Echo)

Description: Echo in a call is the phenomenon of hearing one's own voice reflected back after a delay. There are two types, defined by who hears the echo:

- Talker Echo: This is when the person speaking hears their own voice back after a delay. It typically results from the far-end hybrid or acoustic coupling. For example, if Alice is talking to Bob, and Bob's phone or network reflects Alice's voice back to her, Alice experiences talker echo.

- Listener Echo: This is when the person listening hears their own voice coming back from the other side. It's essentially the same physical echo, but described from the opposite perspective.

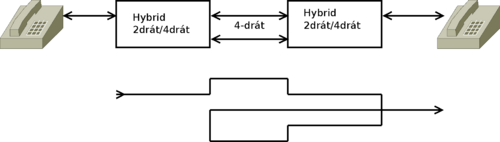

Causes: In traditional PSTN, the main cause of echo is the hybrid – the 2-wire to 4-wire conversion in the analog network. Imperfect impedance matching in hybrids causes a portion of the transmit signal to leak into the receive path, creating an echo. In VoIP contexts, the hybrid echo can occur at analog gateways or digital/analog phone interfaces. Another common cause is acoustic echo: if one party is using a speakerphone or has the handset volume very high, their microphone can pick up the audio from their speaker and send it back.

Impacts on Quality: Echo can be extremely disruptive, particularly when the delay is noticeable. As mentioned, if the echo delay is very short (< ~30 ms), the brain may not distinguish it as a separate sound – it either merges with sidetone or just gives a sense of reverberation. But beyond that, echo is heard as a distinct repetition of your own words, which is very distracting. The loudness of the echo (usually quantified by Echo Return Loss, ERL, which indicates how much the echo is attenuated) and the delay of the echo are the key factors. A loud echo with a long delay is most annoying. Even a relatively quiet echo can be troublesome if significantly delayed.

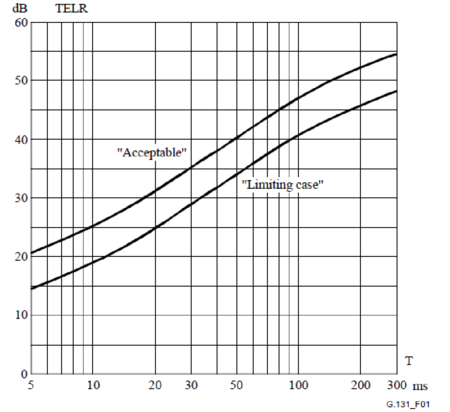

The E-model captures echo impairment in a parameter called Talker Echo Loudness Rating (TELR) which is related to the level of echo and the delay (reflected in the component of delay impairment).

Measurement: Echo is measured by sending known signals and analyzing the returned echo. Key metrics are:

- Echo Return Loss (ERL): how many dB down the echo is compared to the original voice at the point of reflection

- Echo Delay (): the one-way delay from talker to the echo source and back

- Echo Return Loss Enhancement (ERLE): if an echo canceller is present, how much additional attenuation it provides

Mitigation: Echo cancellers are the primary solution. They work by modeling the echo path and subtracting the echoed signal from the incoming audio. All modern gateways and even handsets include some form of echo cancellation as per ITU-T G.168. Ensuring proper impedance matching on analog interfaces reduces initial echo. For acoustic echo, strategies include using good echo-cancelling speakerphones, or in software using acoustic echo cancellation algorithms. If users report hearing themselves, that's an indication the far-end might have echo issues; one may need to troubleshoot that user's device or environment. Also, keeping delays low helps – even if some echo leaks through, if it's under ~50 ms, many users won't notice it strongly, whereas the same level of echo at 150 ms delay would be intolerable.

Non-Linear Distortion

Description: Non-linear distortion occurs when the voice signal is altered due to non-linearities in the system. Unlike simple attenuation or filtering (linear distortions), non-linear effects create new frequency components (harmonics or intermodulation) not present in the original signal. Common causes include:

- Overloading an analog circuit (clipping the waveform)

- Non-linear amplifier behavior (e.g., too high gain causing distortion)

- Quantization effects in certain codecs beyond simple quantization noise

- In VoIP, non-linear distortion could also stem from audio coding algorithms that introduce artifacts

An example in analog domain: if the signal level is too high for a handset amplifier, the peaks of the waveform may saturate, resulting in a clipped, harsh sound. In digital domain, if audio samples exceed the max representable value, you get digital clipping (which sounds like crackling on peaks).

Impacts on Quality: Non-linear distortion generally produces a harsh, unnatural sound. Clipping, for instance, makes speech sound crackly and can reduce intelligibility (soft consonants might get lost if they fall below the clipping threshold relative to noise, while loud vowels get distorted). Users will describe it as "static" or "crackle" or "robotic" depending on the nature. Even mild non-linear distortion can significantly degrade listening MOS because our ears are sensitive to the introduction of frequencies that shouldn't be there or the flattening of peaks (which affects timbre).

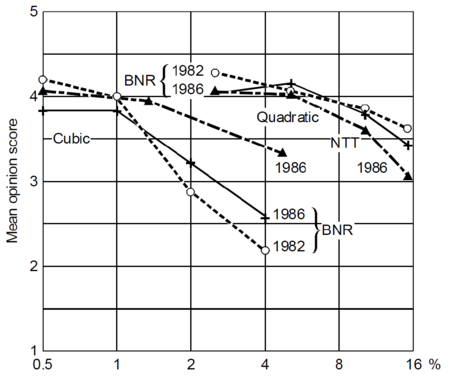

Measurement: In lab environments, one can measure Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) by sending a pure tone and measuring the harmonic content at output. Subjective tests (P.800 listening tests) have documented the impact: for example, earlier research graphed MOS versus distortion level (like cubic or quadratic distortion added to speech). These show MOS falls as distortion increases, often rapidly once distortion goes beyond a few percent THD.

During live network monitoring, detecting non-linear distortion might involve analyzing audio levels versus digital sample clipping or measuring if the waveform peaks are flat-topped. VoIPmonitor has the capability to detect clipping events – essentially moments where the audio waveform reaches the maximum amplitude (0 dBFS) and flattens. Clipping detection algorithms count how many samples are at max amplitude in a row, indicating likely distortion. For example, VoIPmonitor sensors (when enabled) can report if a certain percentage of audio frames were "clipped".

Mitigation: Prevent overload at all stages: ensure levels are set such that typical speech peaks do not saturate analog inputs or DACs. Use AGC (automatic gain control) or limiter circuits carefully to avoid hard clipping (a gentle limiter is preferable if truly needed). In digital, ensure your analog gain staging is correct – e.g., a gateway's input gain too high can clip the ADC. If using codecs, choose ones with sufficient bit depth and low distortion. If clipping is detected in monitoring, adjust the gain on the offending side or advise the user to lower microphone sensitivity.

Codec Compression Impairments

Description: Unlike G.711 PCM (which is a simple waveform quantization), most VoIP codecs use lossy compression to reduce bitrate – examples include G.729, G.723.1, AMR, Opus, etc. These codecs achieve low bitrates by discarding some information and using models of human speech perception. Codec impairments refer to the distortions or losses in fidelity introduced by this compression process.

Each codec has a certain baseline quality in ideal conditions (no packet loss, minimal jitter):

- G.711 (64 kbps PCM) is considered the reference with very high quality (MOS ~4.4–4.5 on narrowband scale)

- G.729 (8 kbps) has inherently lower fidelity – even with no network issues, its best MOS might be around 3.7–4.0 (narrowband MOS) under ideal conditions

- G.723.1 at 5.3k has MOS ~3.6 ideal

- Modern wideband codecs (e.g., Opus at 16–20 kbps) can achieve very high quality (wideband MOS > 4)

These impairments can manifest as slight muffling, robotic or "watery" sound, loss of certain speech subtleties, etc., depending on the codec.

Impacts on Quality: This is a baseline quality limiter. If you choose a low-bit-rate codec, even a perfectly stable network call will have a certain quality level below that of a higher-rate codec. In MOS terms, each codec can be given an Equipment Impairment Factor () in the E-model, which quantifies how much it degrades R-score relative to a hypothetical perfect codec:

| Codec | Ie Value | Approximate Max MOS |

|---|---|---|

| G.711 (PCM 64k) | 0 | 4.4-4.5 |

| G.729A (8k) | 10-11 | ~4.0 |

| G.723.1 (5.3k) | ~15-19 | ~3.6 |

Measurement: Objective voice quality scores like MOS can be predicted for each codec. The E-model uses those values to adjust the expected R (and thus MOS) for the codec in use. Another way is using POLQA or PESQ – these algorithms, given reference and degraded audio, will output a MOS score.

In monitoring, VoIPmonitor by default assumes calls use G.711 (for its MOS calculation) so that it provides a uniform scale for comparison. It notes that G.711 has a maximum MOS of 4.5 (narrowband) and that if a call actually used G.729 (max ~4.0–4.1), the displayed MOS might seem "too high" for that codec. VoIPmonitor allows adjusting for the actual codec if desired, so you can get a realistic MOS reflecting codec choice.

Mitigation: The only "solution" here is to choose an appropriate codec for the scenario. Use a higher-fidelity codec when quality is more important than bandwidth. For HD voice, use wideband codecs (which not only avoid narrowband limitation but often also have lower compression artifacts at similar bit rates due to better algorithms).

Quantization Distortion

Description: Quantization distortion is a specific kind of impairment resulting from the digital representation of an analog signal. In G.711 PCM, the analog waveform is sampled and each sample is quantized to an 8-bit value (μ-law or A-law companding) – this process introduces a small rounding error called quantization noise. For linear PCM of sufficient bit-depth, this noise is very low (for 8-bit logarithmic PCM, effectively ~12-bit linear equivalent in best case, giving around 38 dB signal-to-quantization-noise ratio for small signals, and ~55 dB for loud signals due to companding). In modern terms, quantization noise in G.711 is negligible in perceived quality (hence G.711 is very good).

For historical network planning purposes, the Quantization Distortion Unit (QDU) was established, where one unit corresponds to the quantization distortion that occurs during a single A/D conversion using ITU-T G.711 codec.

Impacts on Quality: For G.711, the quantization noise floor is low enough that users don't perceive "hiss" from it under normal circumstances. Only if you compare to a higher fidelity system or have many tandem stages would the slight quality reduction be noted. On an MOS scale, G.711's quantization is what limits it to MOS 4.4–4.5 (since it's not absolutely transparent to analog original, but very close).

Measurement: Quantization noise can be measured by techniques like Signal-to-Quantization-Noise Ratio (SQNR) for a given input level. The E-model actually has a term for quantizing distortion unit (qdu) in analog network planning (older usage), but when using for digital codecs, one typically doesn't separately calculate quantization impairment – it's lumped into the codec's overall impairment factor.

Mitigation: Ensure using sufficient bit depth for any analog-to-digital conversion. All standard codecs and equipment already do this (8-bit companded PCM is standard; if more fidelity needed, wideband uses 16-bit linear internally before compression, etc.). Avoid multiple unnecessary A/D conversions (each one adds a bit of noise). This is why transcoding between lossy codecs is discouraged unless necessary.

Degradation Factors in IP Networks

All the factors above exist (to varying extents) in any voice system, including the traditional PSTN. However, VoIP over IP networks introduces additional impairment factors stemming from the packet-based, best-effort nature of IP transport. The key network-induced degradations are delay (and its variation), packet loss, and packet reordering. These directly affect voice quality in ways distinct from analog impairments, and they require special handling (like jitter buffers and loss concealment) to mitigate.

| Network Parameter | Conversion | Voice Quality Impact |

|---|---|---|

| IP Transfer Delay (IPTD) | IPTD + source delay + destination delay | Average end-to-end delay |

| IP Delay Variation (IPDV) | Combined with jitter buffer behavior | Adds to delay or causes frame loss |

| Packet Errors | IP + UDP + RTP header errors | Audio frame loss |

| Packet Reordering | May be treated as loss | Audio frame loss |

| Lost Packets | IP loss + all audio defects | Audio frame loss |

| Burst Packet Loss | Depends on burst length | Call interruption |

Delay and Delay Variation (Jitter)

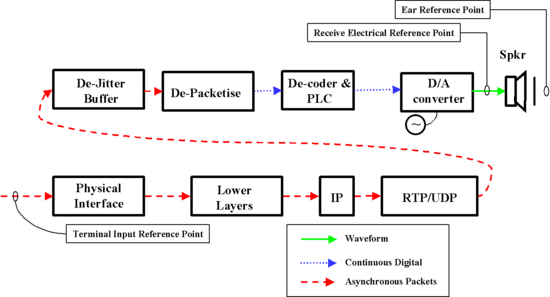

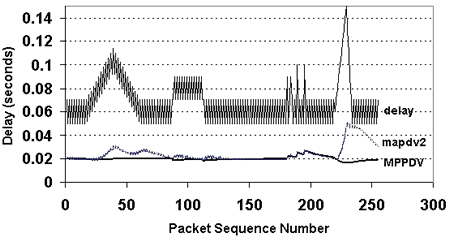

Description: We discussed absolute one-way delay (latency) earlier as a conversational impairment. In IP networks, aside from the base latency, the variation in packet delay is a critical factor. This variation is commonly called jitter. Technically, the term "jitter" can be defined in multiple ways, but in VoIP context it refers to the variability in inter-packet arrival times relative to the original send intervals. Network congestion, queuing, and route changes cause some packets to take longer than others.

For clarity, the precise term defined by standards is Packet Delay Variation (PDV). ITU-T Y.1540 and IETF RFC 3393 define PDV as the differences in one-way delay between selected packets. Many people use "jitter" informally to mean PDV. In this article, we will use jitter to mean packet delay variation, as is common in VoIP discussions.

The Inter-Packet Delay Variation (IPDV) is calculated as:

where is the delay of packet .

The Packet Delay Variation (PDV) relative to minimum delay:

Because voice is real-time, the receiver cannot just wait indefinitely for delayed packets – doing so adds unacceptable latency. Instead, receivers implement a jitter buffer (de-jitter buffer) that buffers incoming packets for a short time and plays them out in steady stream. This buffer absorbs timing variations up to a point. If a packet is delayed beyond what the buffer can absorb (i.e., arrives late after its scheduled playout time), that packet is effectively lost (discarded).

Impacts on Quality: Jitter itself, if managed perfectly by the jitter buffer, only introduces additional delay (the buffering delay). Small jitter is handled by a small buffer, adding maybe 20–50 ms latency, which might be negligible. High jitter either forces a large jitter buffer (adding significant delay, which as we know harms conversational quality) or causes many late packets to be dropped (which is perceived as loss gaps or audio clipping). So the impact of jitter is indirect: it translates into either more delay or more loss, both of which degrade quality.

Jitter buffer types:

- Static (Fixed) – fixed buffer size (simpler, higher latency)

- Adaptive – dynamic buffer size based on network conditions (lower latency, more complex)

Trade-offs:

- Larger buffer → lower packet loss, higher delay

- Smaller buffer → higher packet loss, lower delay

Measurement: Jitter can be quantified in various ways:

- RTP Jitter (as per RFC 3550): A smoothed statistical variance measure that endpoints often report via RTCP

- Packet Delay Variation metrics: ITU Y.1541/Y.1540 define metrics like IPDV, often measured as the difference between some percentile of delay vs a lower percentile

- Mean Absolute Packet Delay Variation (MAPDV2): An average deviation measure

- Jitter Distribution: Tools like VoIPmonitor actually record jitter distribution into buckets – e.g., how many packets were delayed by 0–50 ms, 50–70 ms, 70–90 ms, etc.

VoIPmonitor's approach: it logs detailed jitter statistics per call, and even color-codes a Delay column in its CDRs which shows distribution of jitter events. This allows quick visual identification of calls that had high jitter.

Mitigation: Quality of Service (QoS) mechanisms can reduce network jitter by prioritizing voice packets and preventing long queues. Over-provisioning bandwidth and avoiding slow network segments also helps. On the endpoint side, using an adaptive jitter buffer is crucial. Adaptive jitter buffers dynamically size themselves based on network conditions. They try to balance delay and loss: if jitter increases, the buffer may widen (increasing delay slightly to avoid packet drops). When jitter decreases, they can shrink to reduce latency.

Packet Loss

Description: Packet loss is the failure of one or more packets to reach the receiver. In IP networks, packets can be lost due to congestion (buffers overflow and packets are dropped), routing issues, link errors, etc. In VoIP, any lost RTP packet means a chunk of audio (typically 20ms or so) is missing from the stream. Unlike circuit networks where bit errors might cause slight noise, in packet networks a lost packet results in a gap unless concealed.

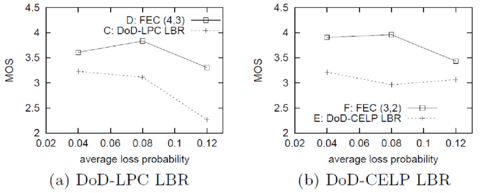

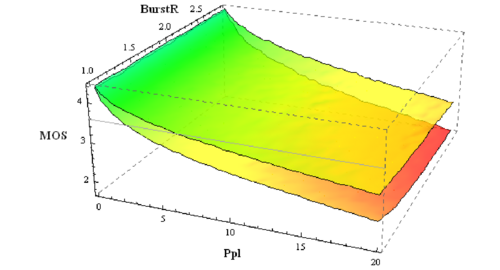

Impacts on Quality: Packet loss is one of the most severe impairments for VoIP. Each lost voice frame results in missing audio. The distribution of losses matters greatly:

- Random isolated losses: A packet here or there is lost. Modern decoders apply Packet Loss Concealment (PLC) algorithms to hide the loss – for example, inserting a copy of the last packet's audio, or some noise, to mask the gap. Humans are quite tolerant to an occasional 20ms concealment.

- Burst losses: Multiple packets in a row lost (e.g., a burst of 100ms of audio missing) is much more damaging to speech intelligibility and quality. A 5% loss rate that comes as one 100-packet burst in a second is far worse than a 5% evenly spread (one packet every 20 packets lost).

This is why two calls with the same average loss can have very different quality. One could have evenly spaced tiny gaps (somewhat tolerable), the other could have entire words or syllables dropping out at once (very annoying).

| Loss Rate | Quality Impact |

|---|---|

| 0-1% | Negligible with good PLC |

| 1-3% | Minor degradation noticeable |

| 3-5% | Noticeable degradation |

| 5-10% | Significant degradation |

| > 10% | Severe degradation, often unacceptable |

The Packet Loss Percentage (Ppl) is calculated as:

The Burst Ratio (BurstR) characterizes loss patterns:

where:

- = Mean Burst Length under random loss model

- = Mean Burst Length actually observed

If BurstR > 1, it indicates more bursty than random loss (BurstR=1 means Poisson loss). The E-model uses BurstR along with average loss to adjust the impairment (since bursty loss is penalized more).

Measurement: Packet loss is measured as a percentage of packets sent that are not received. VoIPmonitor counts lost packets and crucially also records the distribution of consecutive losses. It keeps counters of how often 1 packet was lost, how often 2 in a row were lost, etc., up to 10+ in a row. This allows it to characterize burstiness.

VoIPmonitor's approach: it computes the E-model's packet-loss impairment factoring in burstiness for its MOS scores. If configured, it also can incorporate codec-specific robustness (the Bpl parameter) in this calculation.

Mitigation: The primary way to combat packet loss in VoIP is ensuring network QoS and capacity to avoid congestion losses. Over-provision links or prioritize RTP so losses are minimal. On the application side, use PLC in decoders – all modern VoIP codecs have built-in PLC strategies. Some systems employ forward error correction (FEC) (e.g., redundant audio packets as per RFC 2198, or newer Opus FEC) which add a bit of overhead but can reconstruct lost frames up to a certain percentage.

Packet Reordering

Description: Packet reordering means packets arrive out of their original sent order. In IP networks, reordering can happen when parallel routes exist and packets take different paths, or due to router hardware parallelism, etc. If packets are time-stamped and sequenced (as RTP is), the receiver can detect that a packet with a higher sequence number arrived before a lower one (i.e., an earlier packet was delayed more and came later). Reordering is closely related to jitter – in fact, a severely delayed packet arriving after later packets is one way to define a reorder event.

Impacts on Quality: Minor reordering is usually handled by jitter buffers as well. If a packet comes late but still within the buffer's wait time, it gets inserted in the correct order for playout. The listener never knows it was out of order. If reordering is extreme (packet comes so late that by the time it arrives, its place in sequence has already been played out with a gap or concealment), then effectively that packet is treated as lost (since it missed its playout deadline). So reordering is harmful only insofar as it contributes to effective loss or additional delay.

Measurement: Reordering is measured by counting how many packets were received out of sequence. Tools might track metrics like percentage of packets out-of-order or the extent of reordering. RFC 4737 defines some reorder metrics. In practice, VoIPmonitor looks at sequence numbers and can flag if there are gaps that later filled (implying reorder) or simply count any instance of sequence inversion.

Mitigation: Avoid network scenarios that cause reordering – e.g., sending packets over multiple WAN links without proper sequencing, or using technologies where packet ordering isn't preserved. At the receiver, a sufficiently large jitter buffer will put small out-of-order packets back in order (provided they arrive before the playout deadline).

Summary of Degradation Factors

Having covered the gamut of degradation factors, we see that VoIP call quality is influenced by a mixture of analog, digital, and network phenomena. In summary:

- Classic factors (loudness, noise, frequency response, sidetone, echo, etc.) determine the baseline quality and user comfort

- Codec choice sets an upper limit on fidelity

- Network factors (delay, jitter, loss) often become the make-or-break issues in VoIP, causing even a great codec to sound bad if the network is poor

Voice Quality Measurement Methods

How do we quantify voice quality in a meaningful way? We have described many impairments qualitatively, but network engineers and researchers need numeric measures to evaluate and compare call quality. Broadly, quality can be assessed by subjective methods (asking people for their opinion) or objective methods (using algorithms or formulas to predict opinion). The gold standard is human opinion, but obviously one cannot have people rating every phone call! Thus, several objective models have been developed to estimate call quality.

The most well-known metric is the Mean Opinion Score (MOS). MOS originated from subjective tests but is now often produced by objective estimators.

MOS and Subjective Testing

Mean Opinion Score (MOS) is a numerical measure of perceived quality, typically on a scale from 1 to 5 for voice. The MOS concept comes from having a panel of human listeners rate the quality of speech samples in formal tests. The listeners give ratings according to a scoring system:

| Score | Quality | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Excellent | Imperceptible impairment |

| 4 | Good | Perceptible but not annoying impairment |

| 3 | Fair | Slightly annoying impairment |

| 2 | Poor | Annoying impairment |

| 1 | Bad | Very annoying or nearly unintelligible |

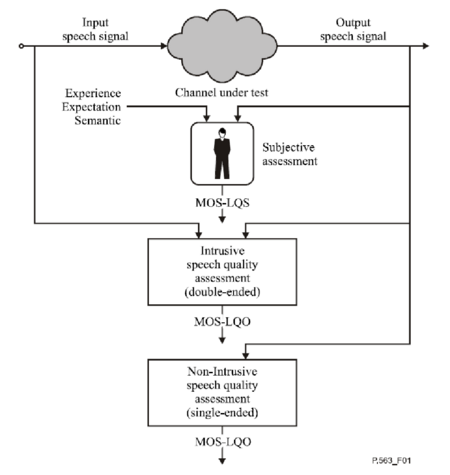

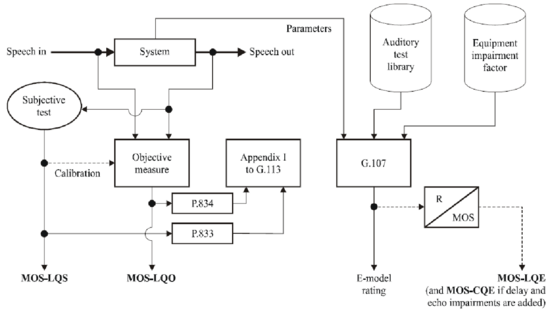

The mean of all listeners' scores is the MOS for that sample/call. Subjective MOS testing is defined by ITU-T P.800, which lays out rigorous methods to conduct listening tests (quiet room conditions, how to select listeners, material, etc.).

Listening-Only MOS (MOS-LQ)

Listening-only tests present participants with speech samples (one side of a conversation, usually just a recording of someone speaking a standardized passage) that have been degraded by the system under test. Listeners then rate the listening quality of what they heard using the MOS scale. This yields MOS-LQ (Mean Opinion Score for Listening Quality). ITU-T P.800 describes this methodology and it's very common for evaluating codecs or one-way audio processing effects.

MOS-LQ mainly evaluates fidelity and distortion aspects (noise, codec clarity, etc.) because the listener is not engaged in a conversation, just hearing the result.

Conversational MOS (MOS-CQ)

Conversational tests involve two people actually talking with each other (often with a prescribed conversational task) over the connection being tested. Afterward, they rate the overall quality of the conversation. This type of test captures the interactivity factors: delay, echo, how two-way impairments affect flow, etc. The output is MOS-CQ (Conversational Quality).

For example, if there is high latency or if echo is present, MOS-CQ will drop, even if the one-way audio fidelity was fine, because the conversation was difficult. ITU-T has recommendations (P.805) that discuss conversational test methods.

Talker MOS and Other Subjective Measures

Another category sometimes referenced is talker opinion – essentially, how the person speaking perceives the quality (from their perspective). Typically, talker-side issues involve sidetone and echo: e.g., if there's an echo, the talker's experience is bad.

Subjective testing is the ground truth, but it's expensive and slow. You need many people, controlled environments, and statistical analysis to get reliable MOS values for a given condition. Therefore, it's not practical for routine monitoring or equipment testing beyond design labs. This led to development of objective models that can predict MOS.

Objective Measurement Techniques

Objective methods aim to estimate voice quality without asking people directly, using algorithms or formulas. They fall into a few categories:

- Intrusive (reference-based) metrics: Require the original clean reference signal and the degraded signal for comparison. Example: PESQ (P.862) and POLQA (P.863).

- Non-intrusive (single-ended) metrics: Only need the degraded signal. Example: ITU-T P.563.

- Parametric (network/model-based) metrics: Rely on known parameters of the call (codec type, loss rate, jitter, etc.) to predict quality. The E-model (ITU-T G.107) is the prime example.

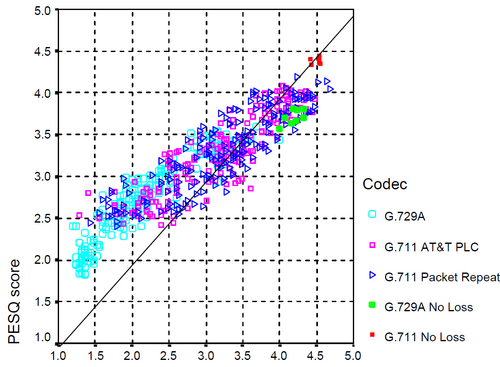

Intrusive Objective Models (PESQ, POLQA)

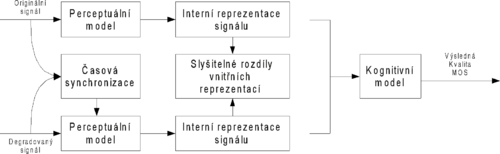

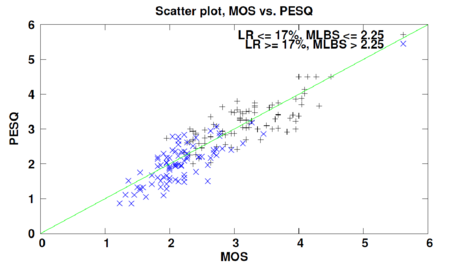

PESQ (Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality), ITU-T P.862, was a breakthrough algorithm standardized in 2001. It takes a reference audio sample (typically a known speech recording) and a degraded sample (the same recording after passing through the system under test), and it outputs a MOS-LQO (Mean Opinion Score – Listening Quality – Objective). PESQ works by aligning the signals, then comparing them using a perceptual model (basically mimicking human auditory processing to see how the degradation would be perceived). The result is a score usually mapped to the MOS scale.

POLQA (Perceptual Objective Listening Quality Analysis), P.863, is the successor to PESQ, standardized in 2011 and updated subsequently. POLQA extends the approach to wideband and super-wideband audio (covering HD voice) and better handles newer distortions (VoIP clock drifts, wideband artifacts, etc.).

These intrusive methods are very powerful, but you need to have the ability to inject and capture reference signals. That means they are used in active test systems: e.g., send a known test waveform through a VoIP call, record it at the far end, and then compute MOS via PESQ/POLQA.

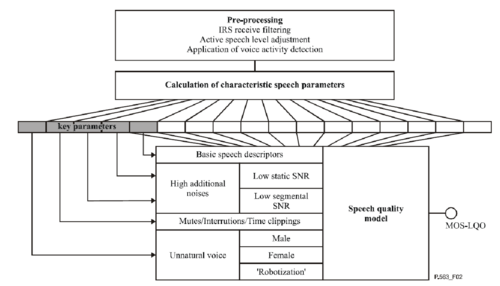

Non-Intrusive Models (P.563)

ITU-T P.563 is a recommendation for single-ended voice quality estimation (often called 3SQM – Single Sided Speech Quality Measure). The idea is to take a recording of a call (just what one person heard) and predict what the MOS would be without needing the reference. P.563 does this by extracting features from the audio: detecting if there's background noise, how much speech is clipped or distorted, etc., and uses an internal model to guess the quality.

While conceptually extremely useful (since you can just tap a call and get a MOS estimate), P.563 had mixed success. It works reasonably for some conditions but is less accurate for others, especially when multiple impairments combine.

Parametric Models (E-model)

Parametric models use known network and codec parameters to predict voice quality without analyzing the actual signal. The prime example is the E-model (ITU G.107) which we will detail in the next section.

VoIPmonitor uses a parametric approach to compute MOS: it essentially implements an E-model calculation internally. Instead of analyzing audio, it takes the measured PDV (jitter) and loss, and knowing the codec (assumed G.711 unless configured otherwise), it calculates the R-factor and then MOS.

The E-Model (ITU-T G.107)

The E-model is a computational model that predicts voice quality (in terms of a user opinion rating) from a set of impairment factors. It was originally designed for transmission planning: to help network planners estimate if end-to-end quality would be acceptable when combining various impairments (like codec choice, echo, delay, etc.). Over time it has also been applied in on-line quality monitoring.

The E-model produces an R-value (sometimes called R-score) that ranges from 0 (extremely poor) to 100 (essentially perfect quality). The formula for the R-value as given in G.107:

Where:

- is the basic signal-to-noise rating (this includes the effects of noise floor, sidetone, and other transducer effects in an ideal network). is about 94 for a typical modern connection with good devices and no noise

- is the impairment factor for simultaneous impairments (like too loud sidetone, or background noise effects)

- is the impairment factor for delay (includes pure delay effects and talker echo if not fully cancelled)

- (or ) is the equipment impairment factor, mainly codec-related (and any packet loss effect combined)

- is the advantage factor, which gives a scoring advantage if the user is in a constrained use case where they expect lower quality. Typically A=0 for normal network planning

Key E-Model Parameters

Codec impairment (): Each codec has a base value. Higher means worse quality. E.g., =0 for G.711, 11 for G.729A, 19 for G.723.1(5.3k), etc.

Packet loss robustness (): A codec parameter indicating how well quality holds up with increasing packet loss. A higher means the codec can handle loss better.

Packet loss rate () and burstiness (): These feed into the formula for . The standard formula:

Essentially, as increases, the effective impairment skyrockets, approaching 95.

One-way delay (T) and echo parameters: E-model calculates as sum of (talker echo impairment) and (pure delay impairment). For T <= 100ms, = 0 (no impairment). As delay goes beyond 100ms, increases gradually.

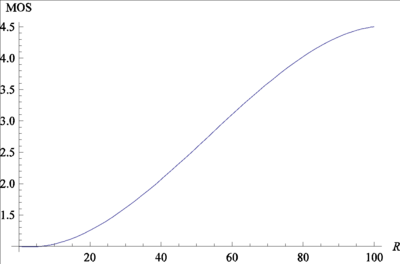

From R-Factor to MOS

After computing R, the E-model provides a mapping to MOS. For narrowband telephony, the mapping is:

This nonlinear polynomial mapping was determined by fitting typical subjective data. Essentially:

- R of 100 maps to MOS ~4.5 (the theoretical max for narrowband)

- R of 0 maps to MOS 1

- R of 94 (which is about max realistic) maps to MOS ~4.4

| R-Factor | MOS | Quality |

|---|---|---|

| 90+ | > 4.3 | Excellent |

| 80 | ~4.0 | Good |

| 70 | ~3.6 | Lower end of acceptable |

| 60 | ~3.1 | Fair |

| 50 | ~2.6 | Poor |

| < 50 | < 2.6 | Very bad |

The E-model is extremely useful because it allows additivity of impairments in a simple way. You can plug in different factors and see their combined effect. Network planners used it to budget how much loss and delay can we tolerate given a codec, etc.

Monitoring Voice Quality with VoIPmonitor

VoIPmonitor is a specialized tool designed to passively monitor VoIP calls on a network and provide detailed metrics and recordings for analysis. Unlike a general packet analyzer (e.g., Wireshark) which can show RTP streams and basic stats for a single call, VoIPmonitor is built to handle high volumes of calls, systematically compute quality metrics, and store long-term data for all calls.

Passive Call Capture and RTP Analysis

VoIPmonitor works by sniffing network traffic (for example, via a SPAN port or network tap) to capture SIP signaling and RTP media packets. It reconstructs call sessions from SIP, then correlates the RTP streams for each call. This is all done non-intrusively; VoIPmonitor is observing copies of packets, not in the call path.

For each call, it can:

- Save the RTP audio to disk (and even decode to audio files if needed)

- Analyze the RTP streams in real-time to gather quality metrics

- Measure exactly how many packets were lost (did not arrive in sequence)

- Calculate the arrival timing of each packet (to calculate jitter)

- Store call records (CDRs) with these metrics in a database

Jitter Analysis and PDV

VoIPmonitor excels at jitter analysis. Instead of giving one opaque "jitter number," it records jitter as a distribution of delay variation events. Specifically, VoIPmonitor logs how many packets fell into delay bins: e.g., 0–50 ms delay, 50–70 ms, 70–90 ms, etc., relative to nominal timing. It defines thresholds (50ms, 70ms, 90ms, 120ms, 150ms, 200ms, >300ms for example bins) and counts how many packets experienced those delays.

This granular data allows the system or the user to query calls not just by "average jitter" but by severity of jitter incidents. For example, the GUI allows filtering calls by PDV events: "find all calls with at least 10 packets delayed > 120ms".

Jitter Buffer Simulation

VoIPmonitor's unique triple MOS output is directly tied to jitter buffer simulation:

- MOS F1 (Fixed 50 ms): Assumes the receiver had a fixed jitter buffer of 50 ms. Any packet arriving more than 50 ms late is considered lost

- MOS F2 (Fixed 200 ms): Same idea, but with a much larger buffer. Fewer packets would miss a 200 ms deadline, so it results in fewer losses but higher latency impairment

- MOS Adapt (Adaptive up to 500 ms): Simulates an adaptive jitter buffer that can stretch up to 500 ms if needed

By comparing these MOS values, an operator can infer:

- If MOS F1 << MOS F2: the network jitter often exceeded 50 ms but stayed under 200 ms

- If all three MOS are similar and high: jitter was low anyway

VoIPmonitor allows configuring whether to assume G.711 for MOS (max 4.5) or adjust for actual codec's max MOS.

Packet Loss Monitoring and Burst Analysis

Packet loss metrics in VoIPmonitor include:

- Total packets expected vs received (to calculate % loss)

- Consecutive loss events counters – you can see if the 2% loss was mostly single packets or chunks

- Loss Rate in intervals: The GUI can show if losses happened in isolated periods or continuous

- You can filter calls by patterns like "calls with > X consecutive packets lost" or "calls with Y% total loss"

This burst analysis is important because of its disproportionate effect on voice quality.

MOS Calculation in VoIPmonitor

VoIPmonitor calculates parametric MOS values:

- It defaults to assuming G.711 codec for MOS, yielding max MOS 4.5 on that scale

- If you configure the sniffer with actual codec info, it can adjust

- It uses the E-model, meaning the MOS reflects network impairments only

- It provides 3 MOS scores (F1, F2, Adapt), which is relatively unique

The manual notes the MOS should not be taken as a definitive absolute, but for filtering and indicating potentially bad calls.

Clipping and Silence Detection

This is a particularly interesting feature of VoIPmonitor that goes beyond standard packet stats. VoIPmonitor can detect audio clipping and silence periods if enabled.

Clipping detection: Clipping is typically detected by checking if the audio signal hits the maximum amplitude for an abnormal duration. VoIPmonitor counts such occurrences. In the filter options, you can search for calls with a certain number of clipped frames. This is valuable because packet stats wouldn't show that – to the network, everything was delivered fine, but the audio quality was bad due to source clipping or distortion.

Silence period detection: VoIPmonitor can also measure the percentage of the call that was silence. You can filter calls by e.g. "calls that had > 50% silence". This could identify one-way audio issues (if one side was silent most of the call, maybe that side's audio didn't get through).

Proactive Quality Management

How a telecom professional would use VoIPmonitor day-to-day:

- Automated Alerts: Set thresholds, e.g., alert if MOS falls below 3 for more than X calls in an hour, or if packet loss > 5% on any call

- Drill-down troubleshooting: When a complaint comes in about a specific call, find that call in VoIPmonitor and examine its detailed stats – jitter graph, loss stats, MOS values, silence percentage, clipping count

- Long-term reports: See trends like average MOS per hour or per trunk

- Compare jitter buffer effects: If many calls show MOS F1 << MOS F2, perhaps endpoints are using too small jitter buffer

Finally, an advantage of VoIPmonitor is that it allows listening to call audio (it can save and even decode to WAV). Numbers and graphs are great, but listening is the ultimate troubleshooting tool: you can literally hear what the user heard.

Conclusion

Delivering high voice quality over VoIP requires understanding and managing many technical factors. Traditional impairments like loudness, noise, and echo still matter in VoIP calls, while network-induced issues like jitter, packet loss, and delay play a dominant role in IP telephony. We have explored each of these factors in detail and seen how they map to measurable parameters and thresholds (often informed by ITU-T standards such as P.800, G.114, G.107, etc.).

To quantify call quality, metrics like MOS provide a bridge between engineering parameters and user perception. Subjective MOS gathered from real listeners is the ultimate benchmark, but objective models – from the signal-based PESQ/POLQA to the parameter-based E-model – enable ongoing assessment of calls without human intervention.

We then focused on VoIPmonitor, illustrating how a modern VoIP monitoring tool applies these concepts. VoIPmonitor passively captures calls and computes a wealth of quality data: jitter distributions, loss patterns, and even audio-based analyses like clipping detection. Its implementation of the E-model yields instant MOS estimates that factor in jitter buffer effects, helping operators pinpoint whether issues stem from network timing, loss, or other sources.

Tools like VoIPmonitor are invaluable in this landscape. They implement the theoretical knowledge (from ITU-T and other research) into practical systems that watch over the network 24/7. By using VoIPmonitor on a VoIP network, one can rapidly correlate objective data with subjective quality – essentially bridging the gap between packet-level events and the human opinion of call clarity.

Armed with the comprehensive coverage of concepts in this guide, technical professionals can better design, troubleshoot, and optimize their VoIP systems. From understanding why a certain call sounded bad (maybe too much jitter causing late packets) to justifying upgrades and QoS policies (by showing improved MOS scores after changes), the knowledge here and the capabilities of monitoring tools will together ensure that voice quality remains high. After all, regardless of technology, clear and reliable communication is the ultimate goal.

External Links

- ITU-T G.107 - The E-model

- ITU-T G.114 - One-way transmission time

- ITU-T P.800 - Methods for subjective determination of transmission quality

- ITU-T P.862 - PESQ algorithm

- ITU-T P.863 - POLQA algorithm

- VoIPmonitor Documentation